New markets embrace an old-world beverage

Sake, Japan’s national beverage, is gaining popularity in and outside of restaurants around the globe. The recipe may appear simple, requiring only four ingredients, but the art of brewing this ancient beverage is anything but. The complexity of flavours and structure comes from the rice (there are more than 100 varieties), the water (often drawn from mountain streams, underground rivers, or deep wells), the yeast, and koji-kin, a special mold that converts the rice starch to sugar.

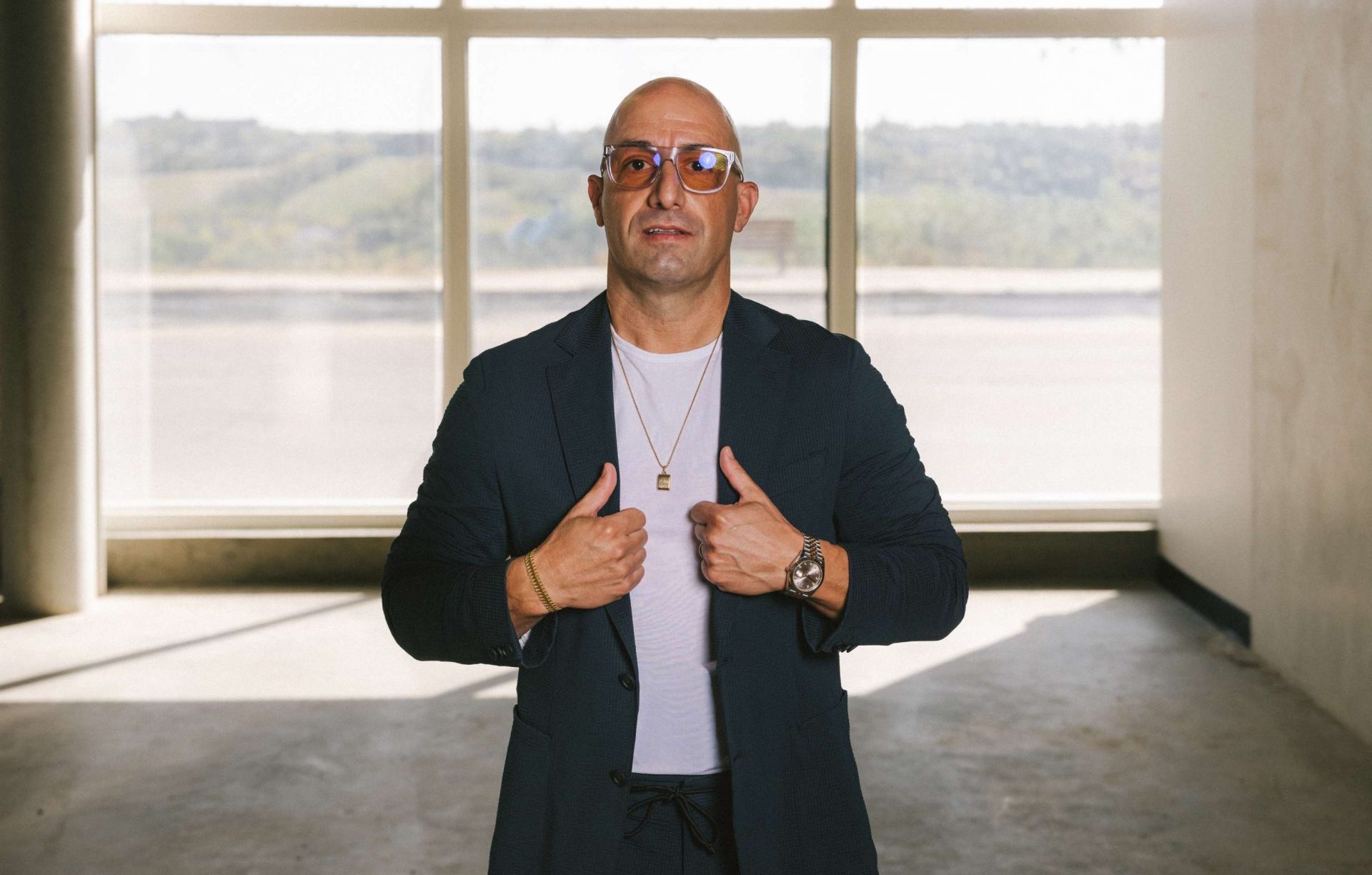

According to Yasuhiro Washiyama, co-managing director of Sakegami and a Level 3 Certified Sake Sommelier, sake’s flavour is best described as unique. “It’s like a puzzle,” he says. “The variety of rice, water, type of yeast, timing of fermentation, and the technique of the brewery make each sake different.”

To appreciate sake, one must understand its style, of which there are many. In our market, the most common styles are junmai, honjozo, ginjo, and daiginjo. “Style” refers to the polishing rate of the rice and whether there is added alcohol. The more the rice is polished (or milled away), the more refined the sake becomes. For example, if the stated polishing ratio is 60 per cent, it means 60 per cent of the original rice kernel remains, and 40 per cent has been polished away. A higher percentage of polishing results in a higher grade of sake with a pure, clean flavour, and a higher price tag. Daiginjo has a polishing rate of 50 per cent, meaning half of the grain has been polished away; however, this does not mean that sakes with a lower polishing rate are of lower quality.

“Many think that daiginjo is best, and they must drink this,” Washiyama says, “but it’s not true.” Each style of sake has a unique flavour profile and distinct characteristics, which creates versatility that allows it to pair with a wide range of dishes.

Junmai is typically polished so that 70 per cent of the grain remains. It is a great place to begin when embarking on a journey into the intriguing world of sake. Honjozo has the same polishing rate as junmai, with one difference: a small amount of distilled alcohol is added to enhance the aroma and flavour. It is an easy-drinking style of sake that is typically more pronounced and fruitier than junmai.

Ginjo (polished so that 60 per cent of the grain remains) and daiginjo styles can have small amounts of alcohol added for enhanced aromas or be junmai style with no added alcohol. Omachi Nakadori is a quality junmai ginjo style, reminiscent of the aromatic white grape Muscat. More of a sweet style of sake, it has musky notes with hints of pear and apricot. Tanaka 1789 is a junmai daiginjo with floral aromas of rose, lychee, and melon, and umami notes of earth and wood. With its natural acidity, it’s often likened to some of the world’s best white wines.

Contrary to popular belief, sake is meant to be enjoyed chilled, not heated, and served with all types of cuisine, not just Japanese food. For Washiyama, changing this perception is a top priority. “Sake is a perfect beverage to pair with food because of umami,” he says, referring to the Japanese word used to describe meaty or mushroom-like flavours, of which many sakes are known to have. With that in mind, more restaurants are offering sake on their menus to pair with foods like pizza, butter chicken, and other spice-forward dishes.

If you’re looking to pair bubbles with a celebration, there’s a sake for that, too. Like Champagne, most sparkling sake is made by a second fermentation in the bottle. The Shichiken is an effervescent surprise with a fine bubble, delicate sweetness, and clean, fresh acidity.

The versatility of an old-world product that easily integrates with modern life makes the future of sake a new and delicious world to explore.