Intuiting the form of human abundance.

Jay Dontae is a twenty-seven year old Edmonton based artist whose previous work in collage, photography, and film has riffed on the visual culture he grew up in: anime, video game art, hip hop culture, and fashion. He’s brought those insights to his work as an educator at the AGA and art course instructor in various venues around our city. But Dontae’s recent direction in painting has instead turned toward elemental human forms. Dontae points to a moment in his first trip to New York that profoundly reoriented his art. Having just visited some of the world’s most illustrious modern galleries, he exited those buildings desperate to achieve an art of permanence. On the street, he found himself captivated by a number of unadorned female mannequins in a shop window. In that moment it became clear to him that “one of the only timeless things in the history of art is the human figure.” Dontae returned home determined to delve into and contort the infinitude of raw feminine form.

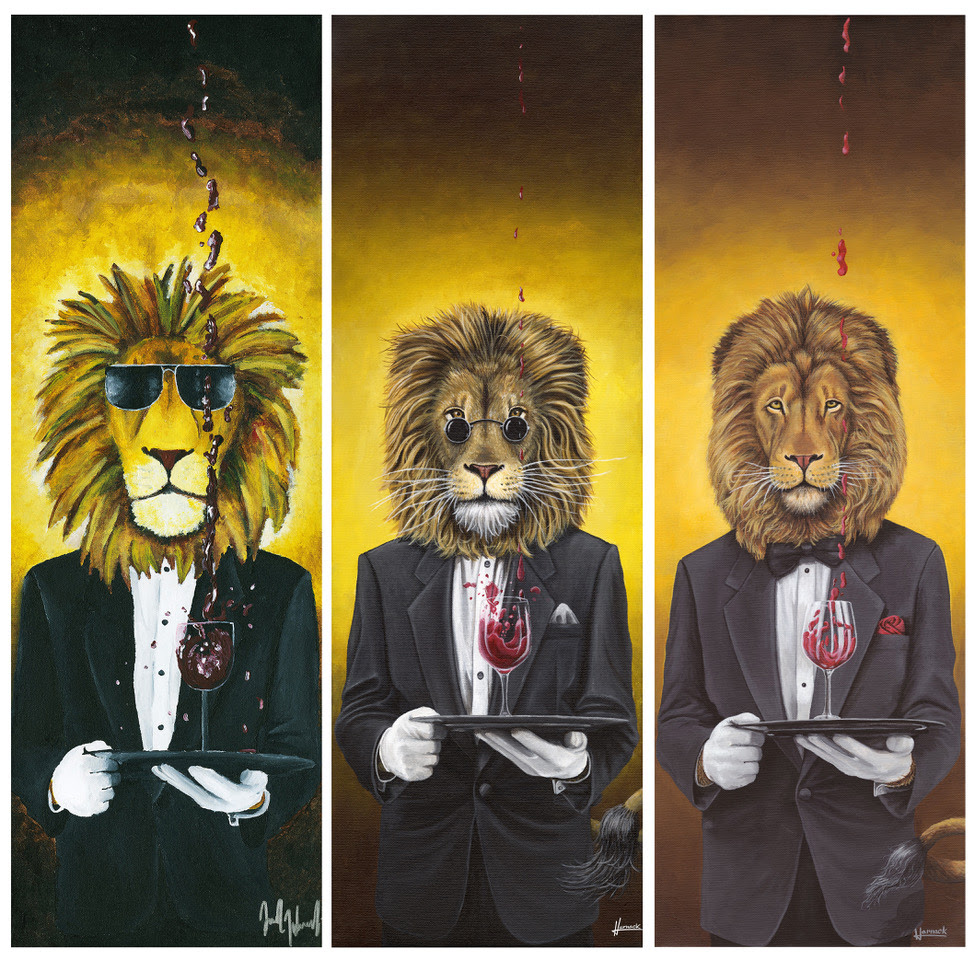

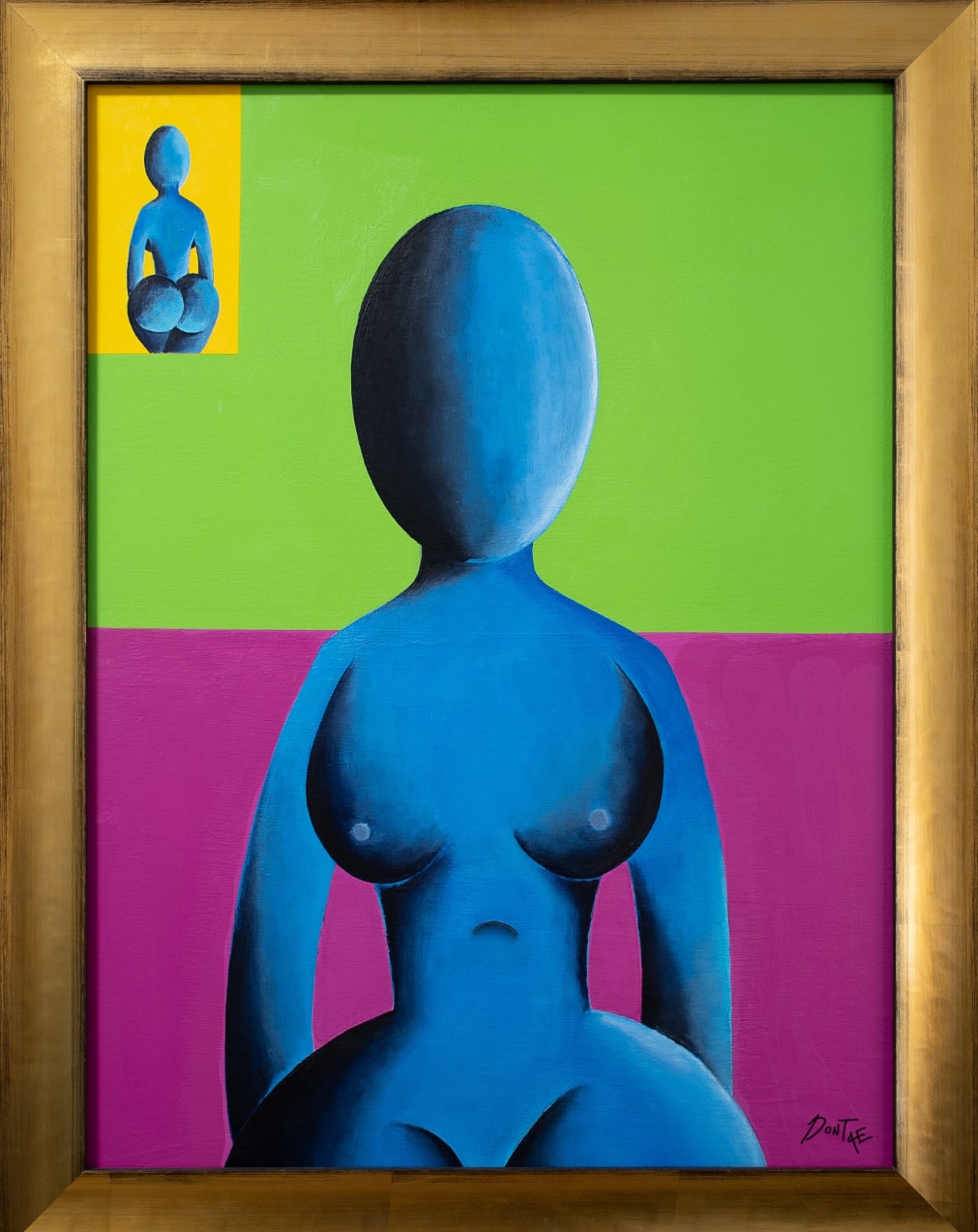

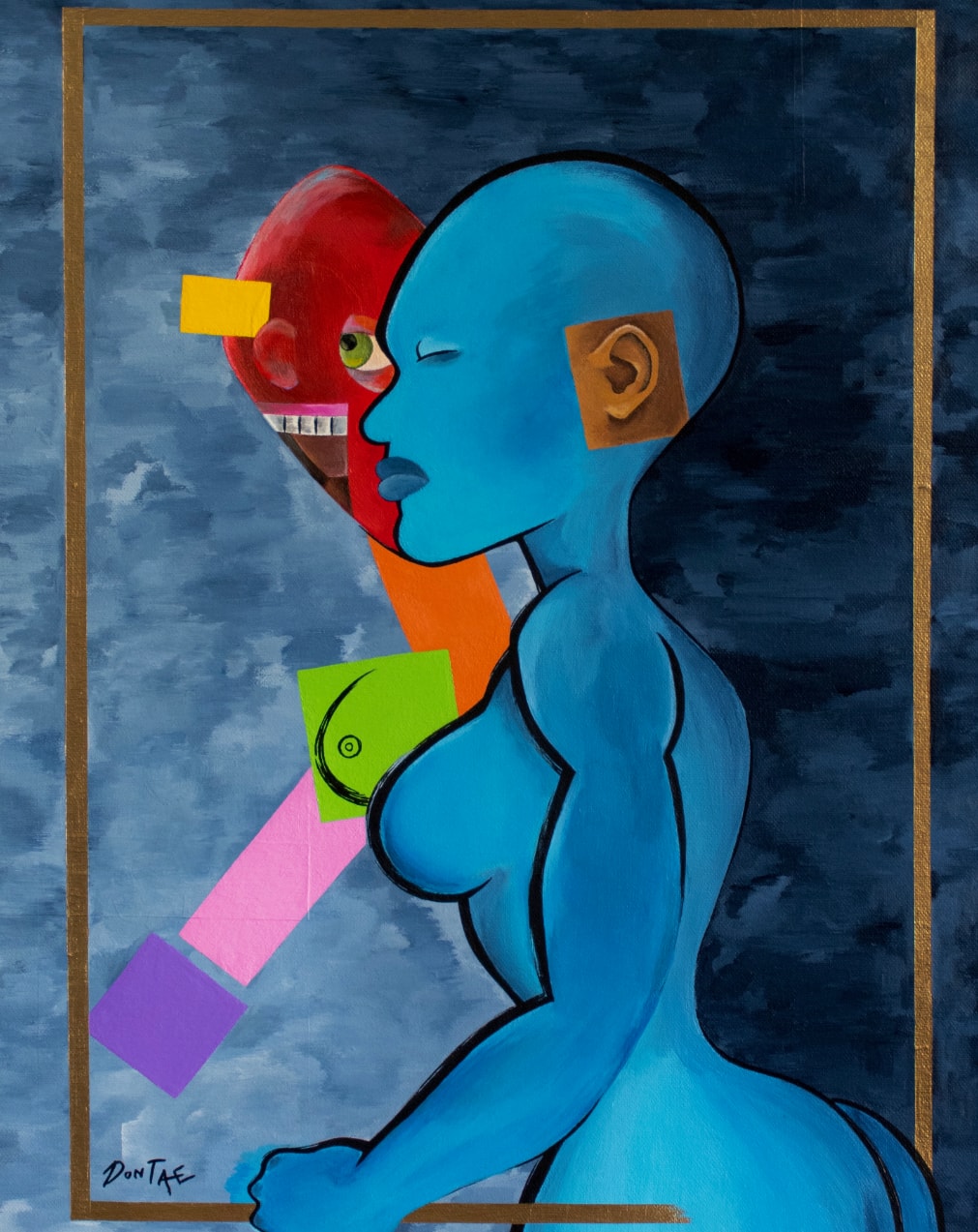

In Heroin(e) I, I tend to overthink, so here’s something simple, and The Dream, we see dream-like female forms elusively twisted or magnified or distilled into totemic volumes. His models are rendered in natural blues redolent of night skies and placid waters juxtaposed against brilliant colours rarely found in nature, chemically derived pigments from our industrial pop culture age. One could argue, perhaps tellingly, that these colours may indeed be found in nature if you consider the flower. It’s a thought provoking clash of organic form and colour against geometric planes of inorganic hues. But Dontae does not approach his work with a meaning in mind—he delights in leaving the possibility of unique interpretation open to his audience. As your correspondent, I feel it’s incumbent on me to venture my own exegesis. To the keen eye it’s clear Dontae’s recent paintings are in conversation with modernists from Picasso to Botero. He explicitly says as much. Yet these paintings also allude to the very earliest artifacts of human sculpture, whether or not intended: the so-called ‘Venus figurines’ unearthed across Eurasia, dating from eleven thousand to thirty-five thousand years of age.

These pocket-sized stone statuettes will be familiar to some, but the prevailing theory has it these figures will be intuitively familiar to every homo sapien, whether you’ve seen them or not. These little round Venus statuettes uniformly feature corpulent maternal bodies with exaggerated breasts, bellies, and buttocks. Many scholars have attempted to explain how this remarkably similar carving could be found scattered over two dozen millenia and across ten thousand kilometers. The newest and now-leading theory comes not from an archaeologist or an art historian but from the highly awarded neuroscientist V.S. Ramachandran. He argues that the voluptuous shape of these figurines is neither a rational nor tradition-based phenomenon. Rather, it is deeply intuited.

In that moment it became clear to him that “one of the only timeless things in the history of art is the human figure.”

By looking at behavioural research into the chicks of seagulls (without going into too much detail here), Ramachandran contended that by exaggerating these life-giving elements of the female physique, homo sapiens were sub-consciously eliciting the powerful feelings we associate with abundance: abundant health, abundant resources, and abundant productivity, both in creating children and in rearing them. These corporeal enlargements provoke the innate attraction we all have to the creative, sustaining, life-giving power of the Mother. Indeed, Dontae confirms that his own figures are not premeditated but rather intuitively felt as he approaches his canvas.

Curiously, the Venus figurines disappear at the very end of the ice age, right as the agricultural revolution begins. Perhaps, for some reason, we see them reappearing anew over the course of the industrial revolution, becoming more wildly contorted, emphasizing new features, and reaching back into our subconscious drives in a whole new way.

Observe how Dontae’s works feature many similar abstractions to the Venus figurines, yet with more slender torsos in our age of over-abundance, stronger arms in our age of female empowerment, and larger free-standing heads in our age of cerebral selectivity. This begs the question: Have we embarked on a new epoch? Or are we trying to recover something we’ve lost? And what do these newfound instincts tell us about how our maternal values have changed and how they’ve remained the same?

Places To Be

See this month's local flavours, products, and services.