21 years of sculpting in the most raw, elemental, and unforgiving medium.

Edmonton’s Rob Willms has devoted the last 21 years to sculpting in one of the most elemental, raw, and unforgiving mediums: iron. His work will be familiar to the observant Edmontonian, as much of it punctuates our urban space. They are the gracefully twisting hulks that seem to rotate as you pass them, works like ‘Long-stemmed optimism’ on 108th and 108th, ‘Slippage’ before the residential tower on 117th street off Jasper, and ‘Head of Hephaestus’ beside the Edmonton Community Foundation, along with many others in the front and back yards of our city’s collectors and patrons.

Willms has much to identify with in the god Hephaestus, Vulcan, the god of sculptors, metallurgy, and fire. And the god born with a limp. At eighteen, Willms’ leg was amputated after a motorcycle accident. He has cohabited with metal every day since, a bionic obverse to the organic gestures he now imbues metal with in his work.

Certainly mythology offers Willms a faithful reference for many of his sculptures. Consider his piece ‘Persephonoia’, a portmanteau of paranoia and Persephone, captive queen of the underworld and the abducted daughter of Demeter. She stands 9’3”, roughly the height the ancients imagined their gods. This towering shock of metal embodies a fear of assault and abduction and rape.

The goddess recoils into the air against the impossible weight of iron. She is outstretched, her twisting spine arching up and away. She looks struck by lightning. She looks clinched in the center by a monstrous fist. Perhaps it is not her at all, but a metal manifestation of that feeling condensing darkling in her heart. It is regal yet raw, an artefact of Persephone’s plight, torn from her mother each autumn and forced back to the underworld. And as the myths have the springs of the land nourished by Persephone’s tears, so the rust on this sculpture offers a final allusion.

The abstraction combines with the magnitude of ‘Persephonoia’ and other of Willms’ large-scale works to remind me of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poem ‘Ozymandias’. They seem like artefacts of our industrial age just uncovered by an archaeologist many millennia from now. You can imagine them marvelling and arguing about what caused these statues to so contort. Was it the slow distortion of catastrophic weather? Or a collapsing office tower? Or a barrage of nukes? What could have so gracefully mutated these beams? The way this hard wrought iron uncrumples with a swivelling thrust feels at once organic and impossible. Regardless, these archaeologists will agree that these iron figures show a human touch—an intent—yet they defy straightforward interpretation. This wild fiction is not so ludicrous when you consider Willms’ process.

Willms’ sculptures take shape gradually over several years, often a decade or more. They begin as tinkerings and loose assemblies tacked together and restructured and retooled without any plan or preconception. At

someprecious Pygmalion moment, however, the whole becomes greater than the sum of its parts and the assembly reveals itself. A volta is reached. It is no longer mere iron, it has become a sculpture, an unfinished sculpture but a sculpture no less. Now it is for Willms to treat and re-treat the work, trying to fulfill that revelation. And then to retreat.

At eighteen, Willms’ leg was amputated after a motorcycle accident. He has cohabited with metal every day since, a bionic obverse to the organic gestures he now imbues metal with in his work.

The sculpture will dwell with him in his studio for years. He will respond to the work in starts and stops, accruing the sensation of the work peripherally, experiencing the figure day by day as it occupies his space, cohabiting. Over time, each angle of sight will be treated as its own opportunity to draw forth the lines and planes that emerge from the preceding vantage point. Eventually, a fully rotating complex of form is brought forth. The twisting sensation I have mentioned above is owing to precisely this process. It results from this revisiting of the sculpture from every angle, infinitesimally, as Willms orbits it for years.

The result is an M.C. Escher-esque folding and unfolding of space that reveals new statements and inquiries from each angle. This is how Willms’ artworks produce a kind of cinematic effect as you rotate around them, like frames in a reel spinning by quickly enough to form a complete image.

Each intervention Willms undertakes must be carefully considered. Iron is not forgiving. The textures evidenced by each intervention become a crucial aspect of each work. The spark-flying scourge of the grinder or the welder’s infernal arc leaves a testament to human choice, either polished like scar tissue or borne proudly like a gnarled battle wound.

The final considerations carry equal gravity: the texture, the colour, and the treatment of the iron’s surface. Some of Willms’ works are so polished as to seem drenched in beeswax while others are so powdered with rust you can smell them before you see them. You shiver to imagine touching the thing, always much hotter or colder than how hot or cold the air is.

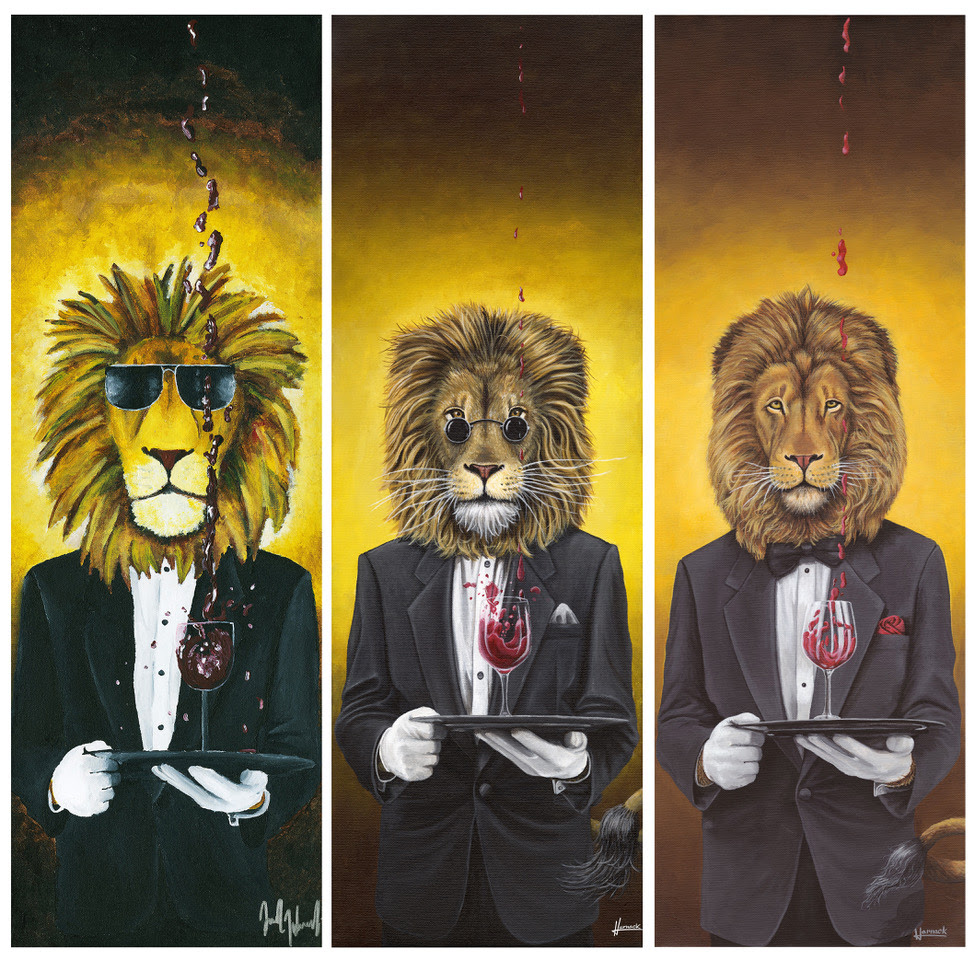

Willms’ most recent medium-scale works, currently exhibiting at the Common Sense Gallery in Edmonton, have been incrementally evolving from fully orbited ‘cinematic’ presentations to squared ‘theatrical’ presentations, as I conceive it. Three such works are especially revealing. ‘Calvaluna’ displays a different scene from every angle, but with a waxy, blunter finish, suggestive of an older camera with less fidelity and a slower frame rate. Calvaluna, or the half calf moon, explores abnormality, the mooncalf being the deformed child the medievals believed the Calvaluna caused. This sculpture furrows and fractures atop tensed tendons straining upward from its base, so steady and proud and resolved, as if to redefine its deformity.

The more recent ‘Two-Fold Self’ twists no less than Willms’ other works, yet with two distinctly opposed vantage points. From the concave viewpoint, I cannot help but see the fog of war, a hollow breastplate rusted raw by rain and blood, so dented and mangled by assault. It is not Athena’s. It is Mars’. And it’s as ferrous as his planet. Violence and its emptiness echo from the cavity. A perfectly placed gash only as wide as a broadsword runs through the sternum clear to the other side. It only reveals itself from this central angle.

From the opposing side, the sculpture immediately strikes me as the convexed mask of Mars’ Corinthian helmet. Having just witnessed the gore and vacuity of its hollow obverse, the rusted mask testifies to the tragedy of arms.

This is my own interpretation—the virtue of Willms’ work is how powerfully suggestive it is. The title itself references Hermann Hesse’s Steppenwolf, perhaps best summarized thus: “Instead of narrowing your world and simplifying your soul, you will have to absorb more and more of the world and at last take all of it up in your painfully expanded soul, if you are ever to find peace.”

Finally, Willms’ most recent work titled ‘Woman Turning Away’ employs a surface that ripples like a tapestry. Here Willms offers us a vantage point that is squared up and singular. We see two players on a stage. After so many fully orbiting works, this unified vantage point produces an immediate emotional impact. For this piece, Willms took two of his previous sculptures and rent them in half, then sutured the halves together along an abdomen of excoriated iron. The rupture is brutal and frank. A heartbreaking turning away motion is masterfully evinced through the mirrored curves, stage right turning her back on stage left. The iron, for all its density, renders the scene so visceral yet so implacable, so incurable. The more time you spend with the piece the more devastating it becomes.

Robert Willms’ sculptures reward the patient eye. They take up too much space to not be contended with. They are as urgent as they are unmoving, and that is a rewarding sight unto itself in a time when all that is solid melts into air at an ever accelerated pace. His works gather up the lifeless refuse of an unfeeling growth machine we hail as Economy and imbues them with life and meaning and human touch. He and several other Edmonton sculptors have turned this redemptive art into an Edmontonian movement that has garnered international attention. It’s a gift to behold.

Places To Be

See this month's local flavours, products, and services.